No safety concerns seen with VPRIV self-administration: Study

Researchers say benefits include independence, flexibility

Written by |

VPRIV (velaglucerase alfa), an enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) for Gaucher disease, can be safely administered by patients or caregivers without posing additional safety risks relative to infusions administered by a healthcare provider, a study showed.

ERT self-administration was also safe in people with Fabry disease who received agalsidase alfa, which is sold as Replagal in some countries but isn’t approved in the U.S. Both drugs are marketed by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, which supported the research.

“Patients self-administering ERT infusions are afforded benefits including independence, flexibility, and control, all of which encourage self-management of their care,” the researchers wrote. “Further research is warranted to support these findings and to explore further the long-term safety and efficacy of ERT self-administration.”

The study, “Safety analysis of self-administered enzyme replacement therapy using data from the Fabry Outcome and Gaucher Outcome Surveys,” was published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. Two of its authors are Takeda employees.

Both Gaucher and Fabry diseases belong to a group of conditions called lysosomal storage disorders, where enzyme deficiencies in lysosomes — cells’ waste disposal centers — cause the harmful accumulation of substances in the body.

Replacing enzymes through infusions

In Gaucher, the deficient enzyme is glucocerebrosidase, which normally breaks down a fatty molecule called glucocerebroside (Gb1) in lysosomes. Gb1 consequently accumulates and causes damage, especially affecting the spleen, liver, and bones, resulting in Gaucher disease symptoms.

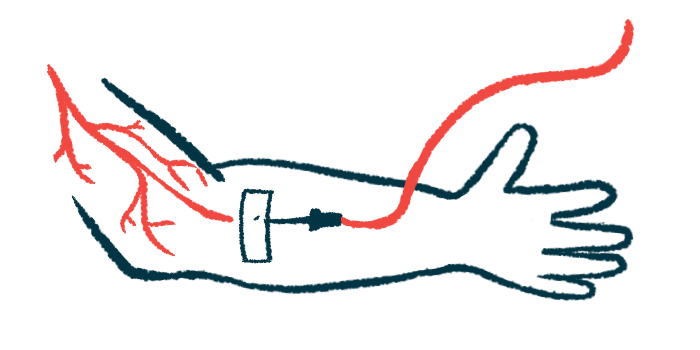

ERT, which supplies the body with a functional version of the faulty enzyme, is a standard treatment approach for lysosomal storage disorders. VPRIV is one such therapy that’s approved in the U.S., European Union, and elsewhere to treat type 1 Gaucher disease, though it’s also sometimes used to treat non-neurological symptoms in other disease types.

These treatments are given via regular infusions into the bloodstream. In many places, including the U.S., they’re administered by a healthcare provider (HCP) in the clinic or at a person’s home.

But protocols vary by country, and some places allow ERT to be self-administered by patients or caregivers if the medication is well tolerated in clinic or hospital infusions and a person is adequately trained. This could offer more convenience for people with Gaucher, who often require lifelong treatment.

The study examined data from two Takeda-sponsored global patient registries to explore the safety of self-administered ERTs, infused by the patient or a care partner.

The researchers looked at the records of 30 people from the U.K. and Israel from the Gaucher Outcome Survey (NCT03291223) registry, in whom VPRIV was self-administered, as well as 784 Gaucher patients who received VPRIV in a standard, HCP-supported setting only.

Of all registry participants who received VPRIV, 3.6% of those from Israel and 23.2% from the U.K. were self-administering. More than 90% of people with Gaucher in each group had type 1 Gaucher.

Data generally showed that self-administration did not raise any new safety concerns. Adjusting for the total amount of follow-up time in each group, results showed that slightly fewer than five adverse events occurred for every 100 years of patient follow-up, regardless of whether the treatment was self-administered or given by an HCP.

Rates of treatment-related, serious, or fatal adverse events and infusion-related reactions were infrequent, and occurred at similar or slightly lower rates in the self-administration group.

The most frequently reported adverse events reported in people who self-administered were skin disorders (13.3%), with the most common serious adverse event being infections (6.7%). No deaths were considered related to treatment.

In both groups, the mean length of treatment before the first adverse event occurred was 4.5-5 years, which the scientists said indicates “that [adverse events] are not likely to arise from inadequate training or poor infusion practices.”

The scientists also looked at data from the Fabry Outcome Survey (NCT03289065), similarly finding that ERT self-administration was generally safe among people with Fabry disease.

“The results of this analysis … support that there are no additional safety concerns with self-administration of the ERTs … versus HCP-supported infusions,” the researchers wrote.

Still, the scientists said the comparison should be interpreted with caution, in part because people eligible for self-administration are those who have shown to tolerate the treatment well in the clinic. Those self-administering could have also underreported their side effects.

“Nonetheless, the results of our analysis suggest that self-administration … has a favorable safety profile and can be a suitable option for many patients,” the team wrote.

Because self-administration practices still vary by country, and because the option is not available everywhere, “countries not yet implementing self-administration practices could benefit from guidance on best practices provided by other countries with established self-administration programs,” the researchers concluded.