Liver Health Needs Constant Monitoring in Gaucher Patients, Study Says

Written by |

Although standard therapies for Gaucher disease (GD) usually reduce liver damage, some forms of treatment — particularly enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) — seem to be linked to a higher incidence of fatty liver disease, a study found.

The findings highlight the importance of constantly monitoring liver health in people with Gaucher, even after they start treatment, the researchers said.

Titled “Liver involvement in patients with Gaucher disease types I and III,” the study was published in the journal Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports.

GD is caused by a mutation in the GBA gene, which leads to the abnormal production of the enzyme beta-glucocerebrosidase. Lacking the functional enzyme results in the accumulation of a fatty substance called glucocerebroside inside immune cells known as macrophages, which then become Gaucher cells.

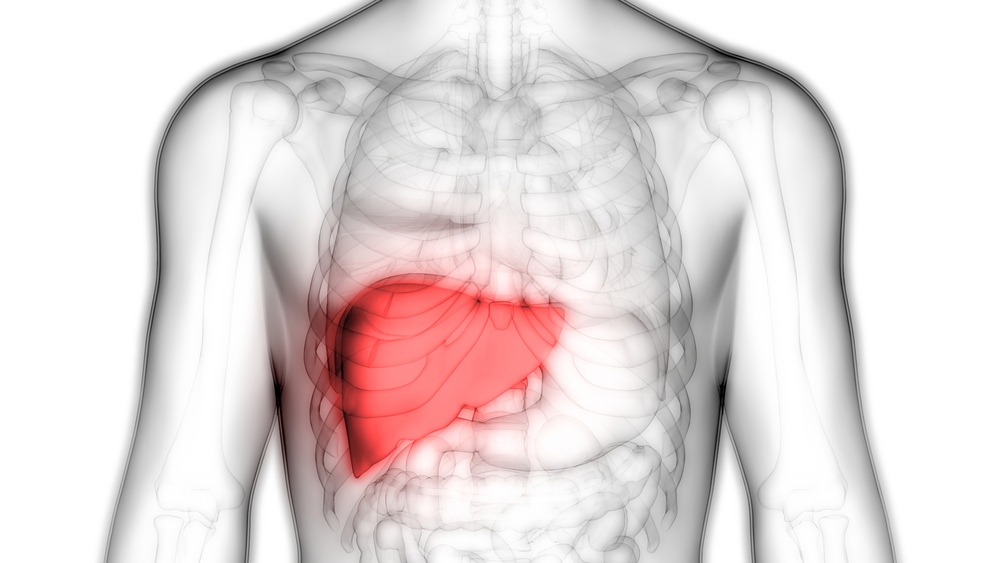

These cells may then enter the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and nervous system, giving rise to symptoms such as liver and spleen enlargement, called hepatosplenomegaly. More recently, liver damage in GD has been associated with other disorders such as fibrosis (scarring), fatty liver disease known as steatosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma or liver cancer.

To evaluate the possible effects of treatment on liver health in people with type 1 and type 3 Gaucher, investigators in Brazil reviewed the medical records of patients who had been followed at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre from 2003 to 2018.

Among the 42 patients (median age 35) included in the study, 39 had been diagnosed with type 1 GD and three with type 3.

Most patients (37) were receiving ERT, while only two were on substrate reduction therapy (SRT). Three patients were not receiving any form of treatment for their condition.

ERT, a lifelong treatment administered into the bloodstream, can help substitute the defective or deficient beta-glucocerebrosidase. Meanwhile, SRT uses small molecules that inhibit the synthesis of the cell membrane component that is broken down by beta-glucocerebrosidase. By reducing the substrate of the enzyme, the levels of the waste products can be reduced.

The median time patients were receiving treatment was 124 months (approximately 10 years).

High levels of liver enzymes, indicating liver damage and inflammation, were found in 68% of the patients prior to the treatment’s start, known as baseline. After treatment, at follow-up, more than half (55%) of the patients continued to have high levels of these enzymes.

Liver enlargement also was seen in 67% of the participants at the treatment’s start, but dropped to 39% at follow-up.

In contrast, the percentage of patients showing signs of fatty liver disease, or liver steatosis, increased from 8% at baseline to 39% at follow-up. Three-quarters (75%) of the patients who had liver steatosis were either overweight or obese.

“ERT is a potent inducer of weight gain,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, it may be difficult to establish whether the high prevalence of steatosis is a manifestation of GD itself, a complication of its treatment, or a comorbidity.”

The researchers also found that seven patients with type 1 GD who had been receiving ERT for a median period of 55 months — four years, seven months — had excessive levels of iron in the liver. That condition is known as iron overload.

Among the eight individuals who underwent liver biopsies, three showed signs of fibrosis, while two had steatohepatitis (a type of fatty liver disease), and one developed liver cancer. With the exception of two patients whose biopsies revealed signs of liver fibrosis before the start of treatment, all other biopsy findings were made after the treatment had begun

“Although treatment [lessens liver] damage, it is associated with an increased rate of steatosis,” the researchers wrote. “This study highlights the importance of a follow-up of liver integrity in these patients.”