Nebraska’s Neena Nizar Seeks Cure for Jansen’s, One of World’s Rarest Diseases

Written by |

Imagine living your whole life with a painful disease so rare that only 25 others worldwide have what you have. And that you’re one of just six such people who’ve made it to adulthood.

Neena Nizar doesn’t have to imagine. The 41-year-old English professor at Metro Community College in Elkhorn, Nebraska, was born with Jansen type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia — also known as Jansen’s disease after Murk Jansen, the Dutch orthopedic surgeon who first observed the illness nearly 100 years ago.

“My geneticist said you could win the national lottery three times over before you’d get a disease like this,” she joked. “And I’m different from the other Jansen’s cases because I don’t have raised calcium levels and phosphate issues, so I’m an anomaly.”

Nizar is founder and president of the nonprofit Jansen’s Foundation. She spoke to BioNews Services — which publishes this website — following a presentation at the NORD Family & Patient Forum in Houston. The June 22 event was sponsored by the National Organization for Rare Disorders, a coalition representing 290 patient advocacy groups, including Nizar’s charity.

Jansen’s disease is caused by a mutation in the PTH1R gene, which contains the information for a protein called parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor (PTH1R), which controls the whole-body levels of calcium. The mutation causes the PTH1R protein to be “turned on” all the time, causing its patients to lose bone faster than they can make it. As a result, the ends of their bones are always soft, and they bend.

“That’s why I was misdiagnosed with rickets or polio for such a long time,” said Nizar, who weighs 90 pounds and measures just under four feet tall.

People with Jansen’s disease have extremely short arms and legs; they also have characteristic facial abnormalities such as an unusually small jaw, receding chin, highly arched roof of the mouth, wide fibrous joints between bones of the skull, and prominent, widely spaced eyes.

“When I was born in Dubai, I had several misdiagnoses,” said Nizar. “There was no Google, no expert opinion back then. The doctor in the room was God. We struggled for most of my childhood without knowing what was wrong.”

Sons led to correct diagnosis

Nizar said she’s had at least 30 surgeries and spent much of her early life in and out of hospitals.

“In Dubai, there wasn’t any accommodation for people with disabilities. I went to a regular school and had to struggle with getting to class. My father had to carry me to class after every surgery,” she recalled. “It was hell, but I had a great family and support system.”

Nizar added: “Everything the doctors said I wouldn’t do, I did. They said I’d never get married. I did. We were in the process of adopting a child because the doctors had said I would never have a child — and that if I did go through the process [of pregnancy], I would not survive.”

But in 2009, Nizar gave birth to a healthy 8-pound boy. She and her American husband, Adam Timm, named their son Arshaan, which is Persian for “good man.” The baby showed no sign of disease until Nizar was pregnant with her second son — about the time Arshaan started walking with his feet turned inward.

“Although he met all his other milestones, I knew something was wrong. They found out he had hypercalcemia [elevated blood calcium] and elevated phosphate levels,” she said. “But the things we were seeing in him had nothing to do with what I had.”

It wasn’t until two years later, when her second son, Jahan (Persian for “savior”) was diagnosed, that all the pieces of the puzzle came together. Sheela Nampoothiri — a pediatric geneticist at India’s Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences who had heard about the ultra-rare condition in Germany — correctly diagnosed Nizar and her sons with Jansen’s disease.

Harald Jueppner, MD, is the chief of pediatric nephrology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The German doctor is also a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, where he’s been leading research on Jansen’s disease since 1995.

“From these rare diseases you gain a lot of understanding,” Jueppner told BioNews by phone from Boston. “If we end up finding a medication that helps Jansen’s patients, there’s a good hope of possibly treating other conditions like hypercalcemia. It may even have an impact on patients with chronic kidney disease.”

Skeletal surgery wasn’t enough

Jueppner knows of about 25 confirmed cases of Jansen’s disease worldwide, with affected individuals living in Brazil, China, France, Germany, Israel, Japan, and the United States. He also said Nizar is one of only two U.S. adults with the condition; the other lives in Wisconsin.

But Jueppner had never actually met anyone with the disease in all the years he had studied it. That changed in February 2016, when he finally came face-to-face with Nizar and her sons at a Rare Disease Day event at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland.

From left: Melinda Burnworth, Arizona volunteer state ambassador for NORD’s Rare Action Network; Neena Nizar, who has Jansen’s disease; and CDR Eleni Anagnostiadis, with the FDA’s Office of Compliance. All three shared a panel at the June 2019 NORD Patient & Family Forum in Houston. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

Half a year earlier, both boys had undergone bilateral osteotomies [surgery for reshaping the bones] and corrective surgeries at Delaware’s Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children to fix their lower legs.

“They had never done surgery on a Jansen’s patient before,” Nizar said. “When my sons were shown the pain chart, they asked me what the smiley face meant. They don’t know what it’s like to live without pain.”

The results were good but short-lived, and “as new bone formed, the bends were back with a vengeance,” as Nizar put it. The surgeries were only temporary fixes to a condition with no cure.

The realization that Jansen’s disease is more than a skeletal condition — it could also lead to kidney failure — led Nizar to form her Nebraska-based foundation in February 2017.

With Nizar’s assistance, bone biopsies were taken from her sons in a lab at the University of California-Los Angeles. Jueppner has also received a $1 million NIH grant to explore the efficacy of an inverse agonist in vitro and in mouse models of the disease that will partially turn off the PTH1R receptor.

With a disease as rare as hers, Nizar — who was named 2018 Nebraska Mother of the Year — knew that traditional fundraising efforts wouldn’t work.

“There are resources available if you can find them. We did all this in two years with less than $10,000. We just worked really strategically,” she said. “Just imagine fundraising for a disease in which your family is 50% of the patient population. That made no sense to me.”

A clinical trial of one

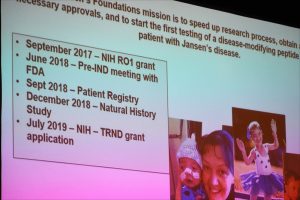

The Jansen Foundation’s mission is quite simple: “To speed up the research process, obtain all the necessary approvals, and start the first testing of a disease-modifying peptide in an adult patient with Jansen’s disease.”

More to the point, Nizar will be that patient.

“We’re now working with the NIH to get toxicology studies in animals,” Jueppner said. “If they fund this, we’ll invite Neena to be the first person to receive the medication in escalating doses.”

He estimated that actual injections won’t happen for at least another two years, though.

“It’s not going to be a trial in the traditional sense. It’s going to be a test run with different doses and over different lengths of time,” Jueppner said. “We want to make sure there are no toxic side effects of this medication in an adult with this condition before giving it to children.”

It might take a few years, but Nizar thinks her persistence will eventually pay off. And even if Jueppner’s potential treatment won’t help her personally, Nizar says she hopes it’ll make life easier for her two sons and the other handful of Jansen’s patients she’s been able to track down around the world.

“In the short time since we started the Jansen’s Foundation, I’ve gotten a fairly good idea as to how we can actually accelerate new drugs and treatments,” Nizar said. “There are so many new rare diseases, and it’s so sad. But at the same time, there’s strength in numbers. We also don’t want to duplicate efforts; we want to hit the ground running.”

She added, “My kids have had surgery every year since 2015. So if we can reduce the number of surgeries, then for us that’s a victory.”