Psychologist Living with Gaucher Strives to Be ‘Role Model of Success’

Written by |

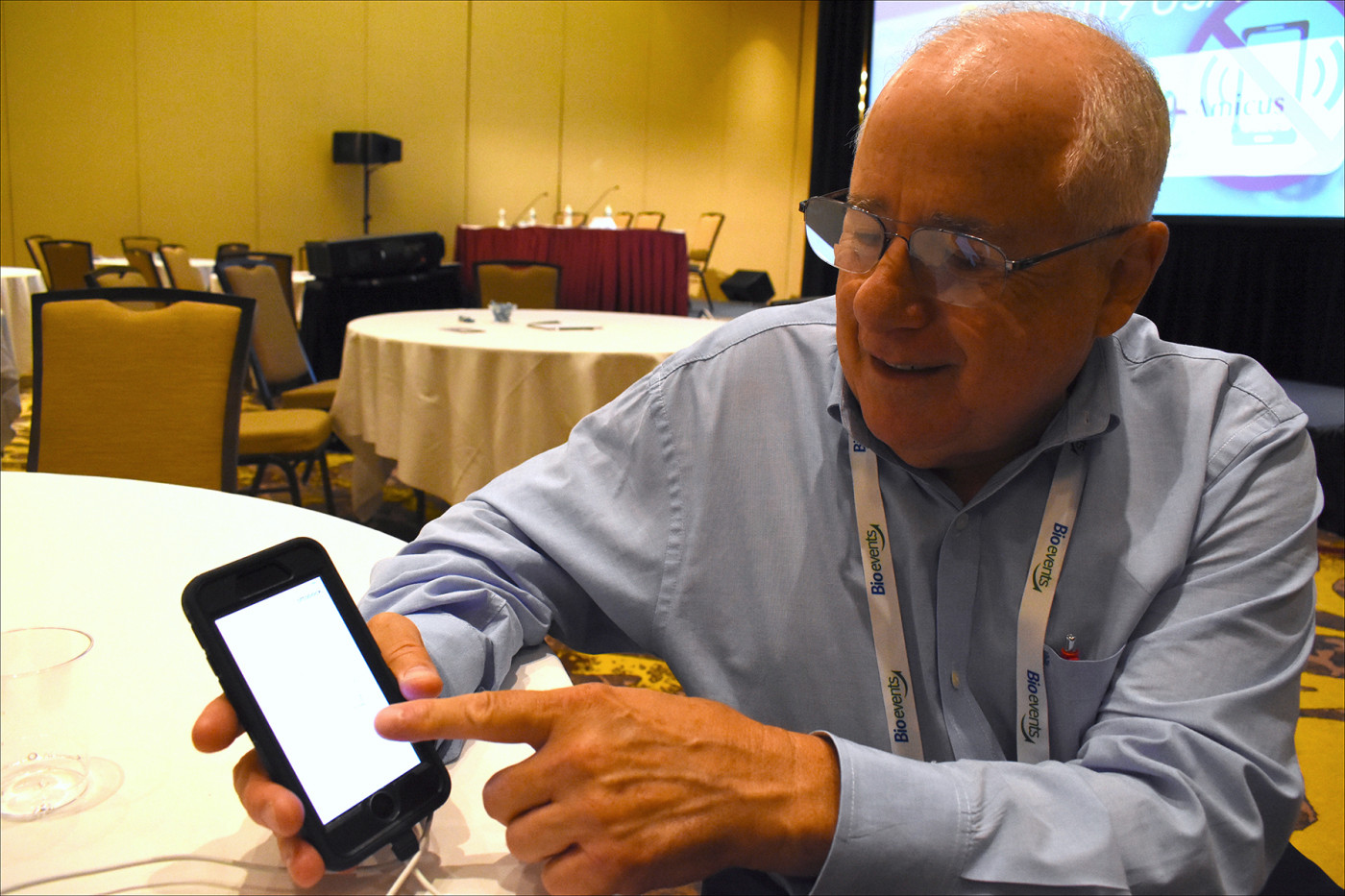

School psychologist Wayne Rosenfield shows the app that controls his artificial leg. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

When school psychologist Wayne Rosenfield was 5 years old, he had an enlarged spleen. Doctors in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts, brushed it off, telling his parents: “He’s just a kid with a larger than normal spleen.”

Later, when the boy complained of nosebleeds, their advice: “Tell him to keep his finger out of his nose.” And when doctors thought that his fatigue and some laboratory markers indicated infectious mononucleosis, they teased him: “Who have you been kissing, young man?”

Then, at age 10, Rosenfield was brought to a hospital in extreme pain. No one knew why, but one diagnostic possibility was leukemia. Because his symptoms seemed to disappear after a few weeks without treatment, doctors concluded that it had been osteomyelitis — and that an injury of some sort had caused the temporary condition.

But a year later, after yet another episode, radiologists reported “dramatic changes in the hip.” More specifically, he had osteonecrosis of the hip, the death of bone tissue.

Finally, at age 15, Rosenfield was referred to a hematologist, who correctly concluded that his patient had Gaucher disease. More than half a century later, Rosenfield wonders why his diagnosis should have been so difficult.

“How could multiple empirical diagnosticians keep getting it wrong for 10 years? In retrospect, diagnosing Gaucher should have been easy, because the correct diagnosis was embedded within the noisy diagnostic picture the whole time,” he said. “The repeated failures were the result of not looking beyond the initial treatment hypothesis.”

Put another way, he suggested, “the most significant question is the one that we do not yet know enough to ask.”

‘Great Necessities’

Gaucher disease, which is nearly always debilitating and sometimes fatal, has no cure. It occurs in roughly 1 in 40,000 live births, and is the second-most common type of lysosomal storage disorder after Fabry disease.

It’s far more prevalent among Jews of Ashkenazi, or Eastern European, descent (about 1 in 450), with as many as 1 in 10 Ashkenazim carrying the mutated gene responsible for the disease.

“The Gaucher population is smart. They know what they need, and they will tell you. In a word, it’s diagnosis,” Rosenfield said. “It takes about seven years from first symptoms to final diagnosis, and historically people with Gaucher symptoms have encountered multiple physicians over 10 or more years prior to receiving a correct diagnosis.”

Rosenfield, 66, spoke about his life with Gaucher at the recent Rare 2019 USA conference in East Brunswick, New Jersey. A clinical psychologist who lives just outside Tampa, Florida, he’s also the author of a 190-page autobiography titled “Great Necessities: A Gaucher Memoir.”

“My book is about my discovery of all the cognitive behavioral things you’ve got to do to survive,” he said. “It’s a major challenge. It’s not easy. My goal is to be a role model of success, but there are times when it’s hard for me.”

Basically, the book explains how the intense narrative of his Gaucher experience became an important asset for a career that involved helping other people in extreme distress.

An avid follower of the U.S. space program who enjoys amateur radio, traveling, and competing in trivia contests, Rosenfield’s only been in “mortal danger” four times in his life.

Amputation by choice

At 18, he had bone surgery to repair the damage caused by the osteonecrosis. “My bleeding was extreme. I lost my entire blood volume during surgery and after,” he said.

When Rosenfield was a 25-year-old doctoral student at the University of Connecticut, he caught infectious mono. He had an acutely hemorrhaging spleen that had to be surgically removed. Even so, he went on to finish his PhD, get married and have two children.

At age 39, Rosenfield developed a bump on his left leg that turned out to be a highly aggressive sarcoma. It wasn’t directly related to Gaucher, but the disease made him vulnerable to this kind of lesion.

“I had a bone transplant, muscle grafting and skin grafting, but I had a poor margin on the tumor. The wound became hopelessly infected and I lost the bone graft,” he said. “A month later, the wound wasn’t healing, so I elected for an above-the-knee amputation.”

Explaining the rationale behind that decision, Rosenfield said that “they could have taken live bone from my right leg and implanted it in my left, but logic told me not to cut into a healthy leg to save another leg that was already extremely compromised. Getting rid of it solved all those problems.”

Even that hasn’t slowed this Gaucher warrior down. Rosenfield walks with the aid of an inexpensive collapsible cane he bought at a pharmacy. But don’t let that fool you.

He’s also outfitted with the Genium X3 — a microprocessor-controlled artificial knee manufactured by Germany’s Ottobock. The waterproof bionic prosthetic system, which retails for $120,000, comes with an app to control configurations and gait settings, and to monitor the power level.

Pain-free and on the go

Rosenfield said his progression of terrible and intense events stopped in 1993 — the year he began enzyme replacement therapy.

He started out on Ceredase (alglucerase), manufactured by Sanofi Genzyme, then switched a year later to Cerezyme (imiglucerase) made by the same company. He stayed on that therapy until 2009, when doctors moved him to VPRIV (velaglucerase alfa for injection), made by Shire‘s human genetic therapies unit.

VPRIV contains the same enzyme as naturally occurring glucocerebrosidase (GCase), which is deficient in Gaucher type 1 patients such as Rosenfield.

“I wouldn’t be without it,” he said of the VPRIV. “It’s an intravenous infusion. I have a nurse come to my house every other week. She mixes the drug and infuses it into my arm. It takes one or two hours, and then we make our next appointment. That’s it.”

These days, Rosenfield said, he’s pain-free and working a nearly full-time schedule. He supervises dissertations in a graduate doctoral program, performs psychological assessments for a group practice, and collects data for a research study on combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder.

He’s also well-known in the Gaucher community and has spoken about the disease at various U.S. conferences and in Canada, Hungary, and Mexico.

Rosenfield explained that intense events lead people to find or develop special strengths in order to survive, which seems to be a part of folk wisdom. Quoting Abigail Adams, this Gaucher survivor sums up the essence of his book in one sentence: “Great necessities call out great virtues.”

Ari Zimran, MD, head of the Gaucher clinic at Israel’s Shaare Zedek Medical Center and organizer of the RARE 2019 USA conference at which Rosenfield spoke, had this to say about his friend: “Wayne is an extraordinary man with an extraordinary life story, as a patient with both Gaucher disease and bone cancer who is functioning extremely well. He’s contributed so much to the Gaucher community. Every time I hear him, I learn more amazing stories about him, and have never stopped being inspired by his positive attitude.”