#ERDC2018 – When Treating Rare Disease Patients, Don’t Overlook Quality of Life, Panel Urges

Written by |

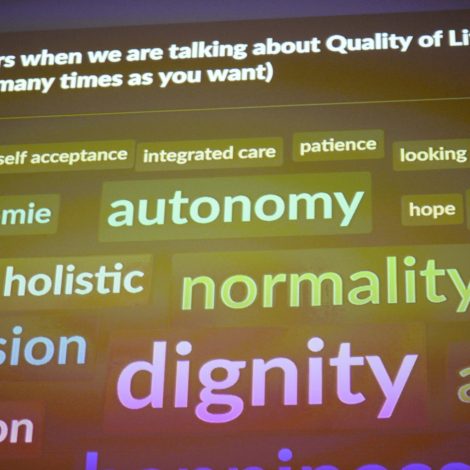

Finding treatments and potential cures for rare diseases is crucial, but so is the quality of patients’ lives — a rather nebulous term that means different things to different people.

“Recently, there’s been much more of a focus on Quality of Life (QoL) issues, real-world evidence and patient-reported outcomes,” said Avril Daly, vice president of the board of directors of Paris-based Eurordis and CEO of Retina International. “This is due largely from the perspective of emerging therapies that have the potential to change our lives for the better. They are seen through the prism of value: is it worth investing in?”

Daly was one of three experts to debate the issue at a May 11 panel during the 9th European Conference on Rare Diseases & Orphan Products in Vienna. That panel itself was the first of four on the subject sponsored by Eurordis and various national rare disease associations.

The European Union defines a rare disease as one that affects fewer than 1 in 2,000 people. By that definition, some 30 million live with a rare disease throughout the 28-member EU. Between 20 and 30 percent of these diseases are not of genetic origin, and in about half of all cases, onset occurs in childhood.

Rare disease patients are often marginalized by society and live with heavy economic, social and psychological burdens, Daly said.

“What’s of value to you might seem very trivial to someone who doesn’t understand your condition,” she said. “Value can be something as simple as going to the bathroom alone, or being able to see in the dark, or playing football with your kids without getting out of breath.”

Eurordis survey spotlights daily struggles

Eurordis recently published a QoL survey of more than 3,000 people in 42 countries with 802 rare diseases. The questionnaire — available in 23 languages and carried out by Rare Barometer Voices — found that more than 70 percent of respondents struggle with such everyday activities as household chores, preparing meals, and shopping.

They also have hearing and vision problems, and trouble maintaining body positions, according to the 40-page report based on this survey, “Juggling care and daily life: The balancing act of the rare disease community.”

In addition, 42 percent of patients and caregivers spend at least two hours a day on illness-related tasks — from hygiene to administering treatments; 30 percent of caregivers each day spend six hours or more on such tasks — with the number rising to 47 percent among caregivers of severely affected patients.

This burden falls disproportionally on women, with mothers comprising 64 percent of all caregivers, followed by spouses of either gender (25%), fathers (6%), and others (5%).

The survey also found that 70 percent of rare disease patients and caregivers were forced to reduce or discontinue their careers (professional activity) due to illness.

Among patients, 37 percent reported often or very often feeling depressed or unhappy, compared to 11 percent of the general population, and 34 percent said they often or very often felt they could not overcome their problems, compared to 8 percent of the general population.

Among the possible reason for this: the stresses of life with a rare disease. In the survey, 54 percent also reported isolation from family or friends “caused or amplified” by their disease; 76 percent expressed “limited professional choices” due to their disease; and 43 percent noted difficulties in basic communication with others, whether in conversation or via emails.

“My fatigue symptoms mean I am virtually unable to work and spend a lot of time resting,” said one woman living in the U.K. “My life is very very limited: I am only 51 but able to do much less than many 75 year olds … I don’t look ill but am very ill with a condition which no one understands or has heard of so get no sympathy.”

Said another in Spain: “The difficulty lies in the impossibility of carrying a routine.”

Working a survey

Sofia Douzgou, MD, a consultant at England’s Manchester Centre for Genomic Medicine, noted the primary role of European Reference Networks (ERNs) in developing QoL indicators.

“The experience of living with a rare genetic condition is vastly more complex than its medical features,” she said. “Any aspect of an individual’s life may be affected. QoL refers to one’s sense of overall well-being, encompassing physical, psychological, emotional, social and spiritual dimensions.”

The ERN for Rare Congenital Malformations and Intellectual Disability, which Douzgou helps supervise, is particularly interested in Angelman syndrome and other congenital malformations.

“We can concentrate on few conditions,” she said, “the ones where we think our network has established expertise and liaise with the relevant patient reps to see whether they are interested in developing new surveys.”

Jakob Bjørner, chief science officer at Denmark’s Optum Insights and a visiting professor at the University of Copenhagen, spoke about different types of surveys available — from generic to disease-specific, from open interviews to structured surveys and ratings — detailing how they might best serve patient groups.

He concluded by warning of “sticker shock” due to licensing costs that might scare off smaller rare disease associations, but urged its members to forge ahead. “Go back and negotiate, even if you don’t have any money at all,” Bjørner said.